the dempster

Highway to the Arctic

Reaching north for 457 miles, the Dempster Highway runs from the Yukon's Dawson City to Inuvik in the Northwest Territories

by Carl Duncan for Tourism Yukon

by Carl Duncan for Tourism Yukon

DAWSON CITY, Yukon -- Three hours north of Dawson, I saw my first Alaska Yukon (or Tundra) moose, the largest in North America. The jagged Tombstone Mountains still filled my rear-view mirror, but the landscape had opened up into an endless carpet of green moss, blue thaw lakes and stunted spruce and Arctic willows that in southern climes, with roots unbound by the permafrost below, would be thick forest.

The big bull stood in the middle of the gravel road eyeing my approach. I stopped not 50 feet from the unperturbed -- and dangerously unpredictable -- creature. He stood a good 7 feet tall at the shoulder, with a rack of broad antlers. As I fumbled for my camera, he turned and loped off, melting into the landscape.

This was one of many surprises I encountered last summer heading toward the Arctic Ocean on the incomparable Dempster Highway; the only public road in Canada that crosses the Arctic Circle. Renowned for the isolated landscape it traverses and the flora and fauna it showcases along the way, the Dempster is not only a unique road trip but an unforgettable wilderness experience.

The big bull stood in the middle of the gravel road eyeing my approach. I stopped not 50 feet from the unperturbed -- and dangerously unpredictable -- creature. He stood a good 7 feet tall at the shoulder, with a rack of broad antlers. As I fumbled for my camera, he turned and loped off, melting into the landscape.

This was one of many surprises I encountered last summer heading toward the Arctic Ocean on the incomparable Dempster Highway; the only public road in Canada that crosses the Arctic Circle. Renowned for the isolated landscape it traverses and the flora and fauna it showcases along the way, the Dempster is not only a unique road trip but an unforgettable wilderness experience.

Reaching north for 457 miles, the Dempster Highway runs from the Yukon's Dawson City to Inuvik in the Northwest Territories, 2 degrees north of the Arctic Circle. For most of that length, the land it crosses bears no sign of human passage or presence: no side roads, no houses, no telephone or power poles, no scars. There is but a single hotel/service station complex midway. On the road, travelers routinely spot grizzlies, black bears, moose, caribou, Dall sheep and many species of birds.

Sitting atop the permafrost and weathering temperatures that can vary as much as 142 degrees, the road surface is entirely gravel, 20 feet thick in places. Well graded and maintained year round, the route is doable by almost any vehicle, including RVs, the family car, and, for the truly fit, bicycles.

I timed my drive to be in Inuvik on the summer solstice, June 21, when the sun wouldn't set again in the Arctic for nearly two months.

I rented an SUV at the airport in Whitehorse, the Yukon's capital, and headed north for 330 miles on the Klondike Highway to Dawson. As the latitude increased, the trees got smaller and the sky got bigger. By the time I reached Dawson, I understood why it's said that the Yukon is where Alaskans go to get away from it all. The entire territory--at 205,345 square miles, about the size of California and Tennessee combined--has just 31,000 people, and I had left 23,000 of those behind in Whitehorse.

Sitting atop the permafrost and weathering temperatures that can vary as much as 142 degrees, the road surface is entirely gravel, 20 feet thick in places. Well graded and maintained year round, the route is doable by almost any vehicle, including RVs, the family car, and, for the truly fit, bicycles.

I timed my drive to be in Inuvik on the summer solstice, June 21, when the sun wouldn't set again in the Arctic for nearly two months.

I rented an SUV at the airport in Whitehorse, the Yukon's capital, and headed north for 330 miles on the Klondike Highway to Dawson. As the latitude increased, the trees got smaller and the sky got bigger. By the time I reached Dawson, I understood why it's said that the Yukon is where Alaskans go to get away from it all. The entire territory--at 205,345 square miles, about the size of California and Tennessee combined--has just 31,000 people, and I had left 23,000 of those behind in Whitehorse.

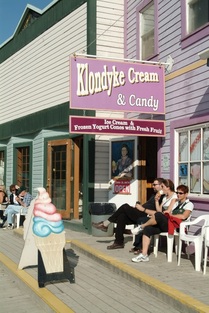

Dawson, with 1,800 people, is the Yukon's second-largest community and sits at the juncture of the Klondike and Yukon rivers. In August 1896, Skookum Jim and some mining buddies found gold just outside Dawson at Bonanza Creek, kicking off the Klondike Stampede. Dawson shot up overnight, adding boardwalks, barrooms, bordellos and boardinghouses.

Mile Post 0 of the Dempster stands just outside Dawson, and, like most Dempster drivers, I tarried for a couple of days in this colorful gold-rush town before setting out and felt transported to another era. Century-old wood buildings sit askew, and bearded placer miners still pawn their pokes of gold dust at the general store on Front Street for a season's worth of grub.

I stayed at a converted turn-of-the-last-century brothel, tried my luck at the casino (proceeds go to historical preservation of the town), and enjoyed the theatrics of the Gaslight Follies at the historic Palace Grand Theatre. Then it was time to go. As the next gas station was nearly 250 miles away, I carefully topped off the tank before turning onto the Dempster and bearing north.

Mile Post 0 of the Dempster stands just outside Dawson, and, like most Dempster drivers, I tarried for a couple of days in this colorful gold-rush town before setting out and felt transported to another era. Century-old wood buildings sit askew, and bearded placer miners still pawn their pokes of gold dust at the general store on Front Street for a season's worth of grub.

I stayed at a converted turn-of-the-last-century brothel, tried my luck at the casino (proceeds go to historical preservation of the town), and enjoyed the theatrics of the Gaslight Follies at the historic Palace Grand Theatre. Then it was time to go. As the next gas station was nearly 250 miles away, I carefully topped off the tank before turning onto the Dempster and bearing north.

I joined half a dozen fellow campers on a scenic traipse over springy moss and crispy lichens. We followed a caribou trail up toward the ridgeline and spotted a colony of reclusive marmots next to a tumbling, ice-fringed mountain stream.

Back at camp, I sat by the river reading a book of poetry by Robert Service. The "Canadian Kipling" lived in the Yukon for eight years and wrote his most famous works in his small log cabin on Eighth Avenue in Dawson (now a museum). Though I read well into the night, there was no need for a flashlight. At midnight the sky was blue, and white clouds cast shadows.

Before the Dempster was built, the only way into Canada's Western Arctic was by bush plane or winter dog sled. The highway was begun in 1958, following a route laid out by native trapper Joe Henry of Dawson. In 1964, the gravel highway (asphalt cannot be used because of the shifting permafrost) had reached only to the 120-mile mark at Chapman Lake. It wasn't until 1979 that the Dempster was officially completed all the way to Inuvik.

The Dempster weaves in and out of the tree line, the tundra beginning where the trees end. "Have you walked on the tundra?" reads an interpretive placard on the roadside. "Try it. It's not as easy as it looks!" I stopped near one of a thousand nameless thaw lakes and got out.

Walking on the spongy sedges, mosses and lichens of the tundra was slow but not difficult. But where the tundra turned into muskeg along the shoreline and in low-lying areas, each footstep sank deep into the boggy vegetation, and cold water seeped over the tops of my hiking boots to soak my socks. I understood then why people here wait for freeze-up before trying any cross-country travel.

As I slogged back through the muskeg, the Arctic terns divebombed me, zooming down with their feet outstretched and squawking fiercely. The Dempster is a birder's paradise, and I had blundered onto a nesting ground. These guys have a 24,000-mile annual migration from here in the Arctic down to the Antarctic and back again.

Back at camp, I sat by the river reading a book of poetry by Robert Service. The "Canadian Kipling" lived in the Yukon for eight years and wrote his most famous works in his small log cabin on Eighth Avenue in Dawson (now a museum). Though I read well into the night, there was no need for a flashlight. At midnight the sky was blue, and white clouds cast shadows.

Before the Dempster was built, the only way into Canada's Western Arctic was by bush plane or winter dog sled. The highway was begun in 1958, following a route laid out by native trapper Joe Henry of Dawson. In 1964, the gravel highway (asphalt cannot be used because of the shifting permafrost) had reached only to the 120-mile mark at Chapman Lake. It wasn't until 1979 that the Dempster was officially completed all the way to Inuvik.

The Dempster weaves in and out of the tree line, the tundra beginning where the trees end. "Have you walked on the tundra?" reads an interpretive placard on the roadside. "Try it. It's not as easy as it looks!" I stopped near one of a thousand nameless thaw lakes and got out.

Walking on the spongy sedges, mosses and lichens of the tundra was slow but not difficult. But where the tundra turned into muskeg along the shoreline and in low-lying areas, each footstep sank deep into the boggy vegetation, and cold water seeped over the tops of my hiking boots to soak my socks. I understood then why people here wait for freeze-up before trying any cross-country travel.

As I slogged back through the muskeg, the Arctic terns divebombed me, zooming down with their feet outstretched and squawking fiercely. The Dempster is a birder's paradise, and I had blundered onto a nesting ground. These guys have a 24,000-mile annual migration from here in the Arctic down to the Antarctic and back again.

Weather can change rapidly up here. As I drove across the tundra, dark rain clouds blew in and the temperature plummeted. By early afternoon, when I reached Eagle Plains at Mile 229, just 22 miles south of the Arctic Circle, snow was blowing across the road. The pass ahead had been closed, and a gate with red flashing lights blocked the roadway. No one would be driving any farther today.

I checked into the hotel, which has a good casual restaurant and a bar with a blue-eyed Alaskan husky as a doorstop. My room was snug and warm, if nondescript, and I slept soundly with black-out curtains drawn against the near-perpetual sunlight. The road opened in the morning, and by noon all traces of the freak late-spring snowstorm had vanished.

The Dempster meets the Arctic Circle at a scenic overlook amid the Richardson Mountains (Mile 252). An interpretive display there claims that the Arctic gets as much solar energy in one 24-hour period in the summer as the equator does. No wonder summer growth is so rapid. Blue lupines, fireweed, foxtails, wild roses and even sunflowers colored the roadside.

About an hour and a half beyond the Arctic Circle, the Dempster enters the Northwest Territories, a vast boreal region even more sparsely populated than the Yukon. The road crosses two mighty rivers, the Peel and the Mackenzie, that flow into the Arctic Ocean. Both have toll-free ferries that run from early morning until late at night.

I checked into the hotel, which has a good casual restaurant and a bar with a blue-eyed Alaskan husky as a doorstop. My room was snug and warm, if nondescript, and I slept soundly with black-out curtains drawn against the near-perpetual sunlight. The road opened in the morning, and by noon all traces of the freak late-spring snowstorm had vanished.

The Dempster meets the Arctic Circle at a scenic overlook amid the Richardson Mountains (Mile 252). An interpretive display there claims that the Arctic gets as much solar energy in one 24-hour period in the summer as the equator does. No wonder summer growth is so rapid. Blue lupines, fireweed, foxtails, wild roses and even sunflowers colored the roadside.

About an hour and a half beyond the Arctic Circle, the Dempster enters the Northwest Territories, a vast boreal region even more sparsely populated than the Yukon. The road crosses two mighty rivers, the Peel and the Mackenzie, that flow into the Arctic Ocean. Both have toll-free ferries that run from early morning until late at night.

(c) Inuvikphotos.ca

(c) Inuvikphotos.ca

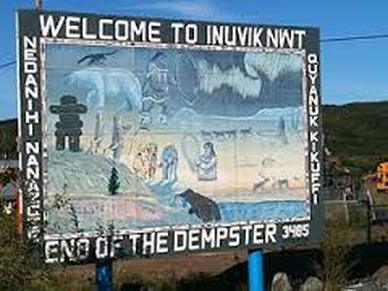

Inuvik sits two hours beyond the Mackenzie ferry. A no-nonsense far-north working town, Inuvik is the life support for the entire Western Arctic, with year-round airport, banks, hotels, and auto and aircraft mechanics. I checked into a snug cabin at the Arctic Chalet, chowed down on a delicious musk ox burger at To Go's for lunch, and oriented myself by spending an hour at the visitor center, with its impressive wildlife and cultural displays.

From late fall to late spring, the Mackenzie River becomes an ice road that continues the Dempster route on to tiny Tuktoyuktuk on the Arctic shore, about 80 miles north of Inuvik. In summer, however, you must fly, and all-day cultural excursions out of Inuvik fill rapidly with tourists who want to go all the way to the Arctic Ocean. The 40-minute flight to Tuk took us low over innumerable blue lakes patched with ice and barren, green-brown tundra puckered like alligator skin. As we neared the Arctic Ocean, I could see icebergs floating in the open water along the shore. A couple of miles north, however, the blue turned to limitless white, and the ice shelf extented to the horizon.

A van met the plane and we toured the little settlement. Ninety percent of Tuk's population of about 1,000 is Inuvialuit (meaning "original people") of the Western Arctic, formerly known to outsiders as Eskimos. Most of the houses are weathered wood with tin roofs; many have dog sleds and a dozen huskies chained in the back. Sheds for smoking fish and rendering whale oil dotted the cove. After a tour of the town and the beach -- where most of the group bowed to tradition and dipped their feet in the frigid Arctic Ocean -- we went to the home of James and Maureen Pokiak for lunch.

Like most residents in Tuk, the Pokiaks hunt, trap, fish and whale for their yearly food supply. Maureen laid out a traditional Inuvialuit lunch of caribou soup, bannock (a kind of hardtack), dried fish, smoked beluga whale meat, whale oil and boiled maktaaq, or muktuk, the narrow layer of blubber between the whale skin and the fat. It tastes something like tofu boiled in rank fish sauce with a touch of bacon drippings. "I boil it about an hour in the smokehouse," she said. The smoke helps keep the bugs away and adds a bit of flavor.

From late fall to late spring, the Mackenzie River becomes an ice road that continues the Dempster route on to tiny Tuktoyuktuk on the Arctic shore, about 80 miles north of Inuvik. In summer, however, you must fly, and all-day cultural excursions out of Inuvik fill rapidly with tourists who want to go all the way to the Arctic Ocean. The 40-minute flight to Tuk took us low over innumerable blue lakes patched with ice and barren, green-brown tundra puckered like alligator skin. As we neared the Arctic Ocean, I could see icebergs floating in the open water along the shore. A couple of miles north, however, the blue turned to limitless white, and the ice shelf extented to the horizon.

A van met the plane and we toured the little settlement. Ninety percent of Tuk's population of about 1,000 is Inuvialuit (meaning "original people") of the Western Arctic, formerly known to outsiders as Eskimos. Most of the houses are weathered wood with tin roofs; many have dog sleds and a dozen huskies chained in the back. Sheds for smoking fish and rendering whale oil dotted the cove. After a tour of the town and the beach -- where most of the group bowed to tradition and dipped their feet in the frigid Arctic Ocean -- we went to the home of James and Maureen Pokiak for lunch.

Like most residents in Tuk, the Pokiaks hunt, trap, fish and whale for their yearly food supply. Maureen laid out a traditional Inuvialuit lunch of caribou soup, bannock (a kind of hardtack), dried fish, smoked beluga whale meat, whale oil and boiled maktaaq, or muktuk, the narrow layer of blubber between the whale skin and the fat. It tastes something like tofu boiled in rank fish sauce with a touch of bacon drippings. "I boil it about an hour in the smokehouse," she said. The smoke helps keep the bugs away and adds a bit of flavor.

McKenzie Delta drum dancers (c) Inuvikphotos.ca

McKenzie Delta drum dancers (c) Inuvikphotos.ca

A small tub of strong-smelling whale oil sat in the middle of the dining table. To the Inuvialuits, muktuk (boiled or raw) is the most coveted of all delicacies, and many dip it in whale oil, which is used here much like some people use butter or mayonnaise. Although American and European whalers of last century used it for lantern oil, they never ate it, and they often suffered from scurvy, a nutritional disease caused by lack of vitamin C.

The Inuvialuits knew nothing about the disease, even though their diet was almost completely without vitamin-rich vegetables. Whale oil, as it turns out, is rich in vitamin C.

Back in Inuvik, the Mackenzie Delta Drum Dancers were celebrating the summer solstice. Today was officially summer, and the sun wouldn't set again in this part of the Arctic for 59 days.

At 1 a.m., I woke with sunlight streaming in my eyes. I looked out and saw the full moon beckoning in the south. It was too much. When would I get another chance to drive across the tundra under the midnight sun?

I grabbed my gear, slipped on a pair of sunglasses, and headed south for Dawson.

The Inuvialuits knew nothing about the disease, even though their diet was almost completely without vitamin-rich vegetables. Whale oil, as it turns out, is rich in vitamin C.

Back in Inuvik, the Mackenzie Delta Drum Dancers were celebrating the summer solstice. Today was officially summer, and the sun wouldn't set again in this part of the Arctic for 59 days.

At 1 a.m., I woke with sunlight streaming in my eyes. I looked out and saw the full moon beckoning in the south. It was too much. When would I get another chance to drive across the tundra under the midnight sun?

I grabbed my gear, slipped on a pair of sunglasses, and headed south for Dawson.

|

All images copyright Tourism Yukon unless otherwise stated

|