SRi Lanka

Three stairways to heaven

By Edward Placidi. Edward is a freelance travel writer/photographer who has lived and traveled in 101 countries, including extended overland journeys across Africa, Europe, South America and Asia. He has penned articles for dozens of newspapers, magazines and websites. When not travelling he is whipping up delicious dishes inspired by his Tuscan grandmother who taught him to cook. A passionate Italophile and supporter of the Azzurri (Italian national soccer team), he lives in Los Angeles with his wife Marian.

The stone steps grew steeper and narrower, climbing ever higher. It seemed they would never end, fatigue and strain tearing at my muscles. It was 4.2 miles – including 5,500 stone steps – straight up to the summit of 7,300-feet Adam’s Peak, Sri Lanka’s legendary pilgrimage site. Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim pilgrims suffered for their religious beliefs, but what possessed me to trudge up this mountain in the middle of the night?

The country’s white-sand, Indian Ocean beaches are popular with tourists, but the cooler highlands are an intriguing world apart with mysterious and magical places, reached after steep hikes. These Sri Lankan stairways to heaven, if you will, are linked to pivotal historical figures and seminal locales including an archeological and geological wonder with UNESCO World Heritage designation, the legendary trader who brought Ceylon tea to the world, and one of the world’s most exotic multi-religion pilgrimage sites.

The country’s white-sand, Indian Ocean beaches are popular with tourists, but the cooler highlands are an intriguing world apart with mysterious and magical places, reached after steep hikes. These Sri Lankan stairways to heaven, if you will, are linked to pivotal historical figures and seminal locales including an archeological and geological wonder with UNESCO World Heritage designation, the legendary trader who brought Ceylon tea to the world, and one of the world’s most exotic multi-religion pilgrimage sites.

Sigiriya

The imposing, massive rock outcrop of Sigiriya looms on the horizon, standing alone high above the tropical forest. It’s no wonder that a former king turned Sigiriya into an impregnable fortress from invaders – or why the Sri Lankans, who are inspired by this natural wonder, assault the mountain in throngs. Down below, it’s a festival-like scene with a maze of stands and hawkers selling everything from hats and postcards to cut fruit and cold drinks. On the rock, many struggle with the precipitous ascent that includes thousands of stone stairs and, at the top, perilous metal walkways clinging to the sheer rock face.

We segued from a sandy path shaded by tall trees to a river crossing by bridge, passed through water gardens built by an early ruler and negotiated a sea of massive boulders populated with scampering toque macaques (Sri Lanka’s endemic monkeys). With the start of stone staircases, the path turned extra steep, and then higher up became a narrow, single-file track. Many faded, often sitting to rest, making passing difficult.

The imposing, massive rock outcrop of Sigiriya looms on the horizon, standing alone high above the tropical forest. It’s no wonder that a former king turned Sigiriya into an impregnable fortress from invaders – or why the Sri Lankans, who are inspired by this natural wonder, assault the mountain in throngs. Down below, it’s a festival-like scene with a maze of stands and hawkers selling everything from hats and postcards to cut fruit and cold drinks. On the rock, many struggle with the precipitous ascent that includes thousands of stone stairs and, at the top, perilous metal walkways clinging to the sheer rock face.

We segued from a sandy path shaded by tall trees to a river crossing by bridge, passed through water gardens built by an early ruler and negotiated a sea of massive boulders populated with scampering toque macaques (Sri Lanka’s endemic monkeys). With the start of stone staircases, the path turned extra steep, and then higher up became a narrow, single-file track. Many faded, often sitting to rest, making passing difficult.

But once on top, the joy was palpable: We poured over the extensive ruins of a 5th-century Sri Lankan capital and lingered over the extraordinary panoramas ‒ many miles in every direction with lakes, peaks and forests.

Sigiriya is one Sri Lanka’s most magical spots and an UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s believed the ancient city was entered by walking into the mouth of a huge statue of a lion. Today, only two enormous paws remain. But that only sparks the imagination of all who climb Sigiriya to envision its wondrous past glory.

Lipton Seat

The journey up to Lipton Seat was a trek through a serendipitous tea fairyland. It was serene, silent, and frozen in time: little has changed since Sir James Lipton, whose name would become synonymous with Ceylon tea, was building his empire here in the late 1800s during British colonial rule.

The hike began at Dambatenne, the tea factory Lipton built in 1890 where some of the original machinery is still in use. I wended and climbed up through a maze of hills, planted with endless, uniformly spaced rows of tea bushes that are perfectly pruned and maintained. Not a leaf appeared to be out of place.

The sea of manicured green is dotted with bursts of color: Tamil women, dressed in a rainbow of bold hues, are picking only the young, tender shoots that have emerged from the bushes. When I asked if I may photograph them, they smiled, blushed and nodded assent.

The steep road up is made much longer by extensive switchbacks. I shortened the distance considerably, however, by taking the vertical stone paths used by the workers that go straight up the tea fields. At the top is where Lipton would go to survey his realm – and to take in what is said to be, on a clear day, the best view in Sri Lanka with 360 degrees of panoramas that reach the waters of the Indian Ocean. I was not so lucky; clouds obscured vistas in three directions. But to the east, I enjoyed a dramatic view of jagged black peaks protruding from puffy white clouds and framed by the intense green hills as I sipped a cup of – what else but – Lipton’s brew at the small tea shop at the summit.

Sigiriya is one Sri Lanka’s most magical spots and an UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s believed the ancient city was entered by walking into the mouth of a huge statue of a lion. Today, only two enormous paws remain. But that only sparks the imagination of all who climb Sigiriya to envision its wondrous past glory.

Lipton Seat

The journey up to Lipton Seat was a trek through a serendipitous tea fairyland. It was serene, silent, and frozen in time: little has changed since Sir James Lipton, whose name would become synonymous with Ceylon tea, was building his empire here in the late 1800s during British colonial rule.

The hike began at Dambatenne, the tea factory Lipton built in 1890 where some of the original machinery is still in use. I wended and climbed up through a maze of hills, planted with endless, uniformly spaced rows of tea bushes that are perfectly pruned and maintained. Not a leaf appeared to be out of place.

The sea of manicured green is dotted with bursts of color: Tamil women, dressed in a rainbow of bold hues, are picking only the young, tender shoots that have emerged from the bushes. When I asked if I may photograph them, they smiled, blushed and nodded assent.

The steep road up is made much longer by extensive switchbacks. I shortened the distance considerably, however, by taking the vertical stone paths used by the workers that go straight up the tea fields. At the top is where Lipton would go to survey his realm – and to take in what is said to be, on a clear day, the best view in Sri Lanka with 360 degrees of panoramas that reach the waters of the Indian Ocean. I was not so lucky; clouds obscured vistas in three directions. But to the east, I enjoyed a dramatic view of jagged black peaks protruding from puffy white clouds and framed by the intense green hills as I sipped a cup of – what else but – Lipton’s brew at the small tea shop at the summit.

Lipton Seat is a highlight of a visit to Sri Lanka ‒ wrapped in a time warp. Life in the verdant hills of tea bushes is a taste of ongoing history. The tea is still picked by hand by Tamil women. Children still attend tea estate schools (where I filmed them reciting lessons). The legacy of Lipton and the tea industry he spearheaded remains. And taking the fascinating tour of Dambatenne Tea Factory reveals that the multi-step process of turning young green leaves into dry, packaged tea continues little changed to this day.

Adam’s Peak

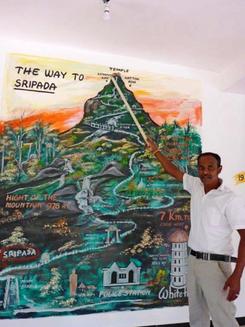

After dinner, Niman gathered his guests around the eight foot-tall illustrated map of the mountain and began his lively and cheeky dissertation on climbing Adam’s Peak. The diverse group, including Buddhists from Indonesia and 20-something Europeans, listened in awed silence. Establishing his credentials by professing to have hiked the peak 1,500 times, he described the route in detail, including the landmarks we’d pass, and when, the daunting stairs (all 5,500 of them) and what we’d find on top, (“watch out for pickpockets preying on pilgrims”).

Then everyone was off to bed, a scene playing out at every hotel and guest house. We were there for one reason, to climb the peak, and we all set out by 2:30 am to be sure of reaching the top for the sunrise.

Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak) is not only a soaring natural landmark reminiscent of the Matterhorn, but also one of Sri Lanka’s most revered places. The footprint discovered on the summit is claimed as Buddha’s by Buddhists, the god Shiva’s by Hindus and as Adam’s by Muslims (his first step after being tossed from paradise). The vast majority of pilgrims, however, are Buddhists.

Adam’s Peak

After dinner, Niman gathered his guests around the eight foot-tall illustrated map of the mountain and began his lively and cheeky dissertation on climbing Adam’s Peak. The diverse group, including Buddhists from Indonesia and 20-something Europeans, listened in awed silence. Establishing his credentials by professing to have hiked the peak 1,500 times, he described the route in detail, including the landmarks we’d pass, and when, the daunting stairs (all 5,500 of them) and what we’d find on top, (“watch out for pickpockets preying on pilgrims”).

Then everyone was off to bed, a scene playing out at every hotel and guest house. We were there for one reason, to climb the peak, and we all set out by 2:30 am to be sure of reaching the top for the sunrise.

Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak) is not only a soaring natural landmark reminiscent of the Matterhorn, but also one of Sri Lanka’s most revered places. The footprint discovered on the summit is claimed as Buddha’s by Buddhists, the god Shiva’s by Hindus and as Adam’s by Muslims (his first step after being tossed from paradise). The vast majority of pilgrims, however, are Buddhists.

The path up is lit with fluorescent tubes and dotted with kiosks selling hot food and tea, tchotchkes and warm clothing. During the December-March season, there’s a nightly parade of pilgrims – more than 100 the night I was there. The path was a teaser, rambling along at a gentle incline at first, lulling me into complacency, before beginning to climb a little, then more, and more. The steps are widely spaced at first but become progressively sheerer and narrower. After thousands of steps, even the fittest hikers feel the effects: my pace slowed to a trudge, breath shortened with each step, legs began to ache, strength waned. As Niman recounted, over the years many pilgrims have been evacuated from the mountain on a stretcher carried by porters after a heart attack or terrible fall.

Suddenly, I could see the summit, only a few dozen steps ahead. I had made it, in just 2 ½ hours. Then it hit me: a fierce, freezing wind that penetrated to the bone. I crammed into one of the few sheltered – and crowded – spots and shivered awaiting the sunrise.

Pinks and reds streaked the sky first, giving way to pale oranges before a blazing yellow ball broke the horizon. Pilgrims were madly capturing the spectacular 360-degree panoramas with their phone cameras (incongruously, it was Buddhist monks who had the professional cameras with telephoto lenses). The sun’s emergence brought almost instant warmth and a glorious, bright and clear morning of shimmering colours.

Was Adam’s Peak worth the exertion, loss of sleep, aching legs and knees, the brutal cold? Absolutely. It was a seminal experience that defined my trip to Sri Lanka, a spiritual as well as physical journey with people from many nations, connecting with the country’s multi-cultural persona. Plus, for the rest of my life I can say I climbed to the spot of Adam’s first step after being ejected from the Garden of Eden.

For more information on visiting Sri Lanka go to http://www.srilanka.travel

Suddenly, I could see the summit, only a few dozen steps ahead. I had made it, in just 2 ½ hours. Then it hit me: a fierce, freezing wind that penetrated to the bone. I crammed into one of the few sheltered – and crowded – spots and shivered awaiting the sunrise.

Pinks and reds streaked the sky first, giving way to pale oranges before a blazing yellow ball broke the horizon. Pilgrims were madly capturing the spectacular 360-degree panoramas with their phone cameras (incongruously, it was Buddhist monks who had the professional cameras with telephoto lenses). The sun’s emergence brought almost instant warmth and a glorious, bright and clear morning of shimmering colours.

Was Adam’s Peak worth the exertion, loss of sleep, aching legs and knees, the brutal cold? Absolutely. It was a seminal experience that defined my trip to Sri Lanka, a spiritual as well as physical journey with people from many nations, connecting with the country’s multi-cultural persona. Plus, for the rest of my life I can say I climbed to the spot of Adam’s first step after being ejected from the Garden of Eden.

For more information on visiting Sri Lanka go to http://www.srilanka.travel

|

Images copyright of the Author

Click on any image to enlarge it |

Want more on Sri Lanka? Check out Sri Lanka Tour