Traveling the ‘New’ Silk RoaD

By Edward Placidi. Edward is a freelance travel writer/photographer who has lived and traveled in 101 countries, including extended overland journeys across Africa, Europe, South America and Asia. He has penned articles for dozens of newspapers, magazines and websites. When not travelling he is whipping up delicious dishes inspired by his Tuscan grandmother who taught him to cook. A passionate Italophile and supporter of the Azzurri (Italian national soccer team), he lives in Los Angeles with his wife Marian.

When I told the owner of Jahongir Hotel in Samarkand how much I was enjoying my travels in Uzbekistan, he had a succinct, arguably self-evident, response: “Hospitality is in our blood. We have been hosting people from many different lands and cultures since ancient times.”

Uzbekistan conjures up evocative images of mysterious bazaars and snaking camel caravans laden with goods crossing endless deserts. It was the heartland of the legendary Silk Road, a central meeting point where traders and merchants from East and West converged. The fabled trio of Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva were not only great trading hubs but also architectural epicenters of their time where great conquerors and leaders vied with each other to construct ever-more impressive monuments that would be living testimonials to their rule.

Today, this historical legacy and diplomatic savvy have come full circle: I discovered people who are among the most friendly, welcoming and helpful anywhere, and was wowed by stunning architectural grandeur that has been largely restored to its former glory. This potent combination has created a ‘new’ Silk Road that is attracting travelers, not just from East and West, but from across the planet. And it’s so easy to experience because the spectacular monuments and sights are protected within tourist-friendly, pedestrian-only walking areas in the old centers of Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva, which are connected by high-speed trains. Visiting the trio is a nostalgic immersion in a storied past that sparks the imagination.

Uzbekistan conjures up evocative images of mysterious bazaars and snaking camel caravans laden with goods crossing endless deserts. It was the heartland of the legendary Silk Road, a central meeting point where traders and merchants from East and West converged. The fabled trio of Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva were not only great trading hubs but also architectural epicenters of their time where great conquerors and leaders vied with each other to construct ever-more impressive monuments that would be living testimonials to their rule.

Today, this historical legacy and diplomatic savvy have come full circle: I discovered people who are among the most friendly, welcoming and helpful anywhere, and was wowed by stunning architectural grandeur that has been largely restored to its former glory. This potent combination has created a ‘new’ Silk Road that is attracting travelers, not just from East and West, but from across the planet. And it’s so easy to experience because the spectacular monuments and sights are protected within tourist-friendly, pedestrian-only walking areas in the old centers of Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva, which are connected by high-speed trains. Visiting the trio is a nostalgic immersion in a storied past that sparks the imagination.

In Khiva, the massive bastions have been completely rebuilt, turning the small citadel and UNESCO World Heritage Site into an imposing landmark. Khiva has been described as an ‘open-air museum’ because of the many ancient monuments concentrated in the small, easily walkable center, but the imposing walls once protected an infamous and bustling slave market – the biggest in Central Asia ‒ notorious for its brutality.

For an unbridled panorama of Khiva, with its skyline of colorful tiled domes and soaring minarets, climb up to The Watchtower. Stairs behind the throne room in the royal fortress lead up to the aerie, the views especially glorious in the orange-tinted light of sunset.

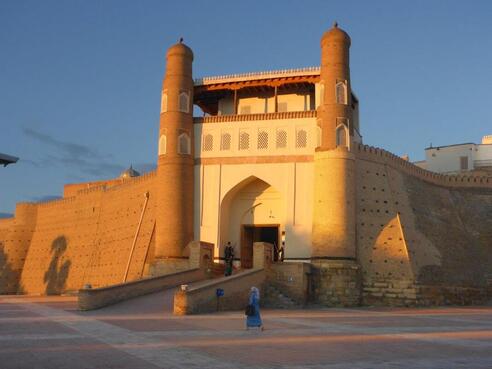

Standing guard over Bukhara from a hilltop perch, The Ark is the city’s oldest structure, dating from the 5th century. The commanding royal residence and citadel was almost totally destroyed in 1920 by Red Army bombs, and nearly a century later remains mostly a ruin except for the resurrected walls and royal quarters.

For an unbridled panorama of Khiva, with its skyline of colorful tiled domes and soaring minarets, climb up to The Watchtower. Stairs behind the throne room in the royal fortress lead up to the aerie, the views especially glorious in the orange-tinted light of sunset.

Standing guard over Bukhara from a hilltop perch, The Ark is the city’s oldest structure, dating from the 5th century. The commanding royal residence and citadel was almost totally destroyed in 1920 by Red Army bombs, and nearly a century later remains mostly a ruin except for the resurrected walls and royal quarters.

At Bolo-Hauz Mosque ‒ the baby of ancient Bukhara at just 307 years old ‒ a traditional Central Asian architectural form reaches its zenith: a towering forest of painted and carved wooden columns are juxtaposed with an intricately worked, vaulted wooden ceiling and bright blue, white and turquoise tile work. It is one of several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in historic Bukhara.

In addition to its architectural heritage, Bukhara also is the shopping capital of the new Silk Road. A sea of vendors is embedded in and around the historic buildings, selling everything from traditional jewelry and hand-made carpets to carvings, silk scarves and clothing, and colorful drawings. You can watch artists, carpet-weavers, tailors, potters and other artisans at work here, and buy directly from them.

The legacy of one of the greatest – and most brutal – conquerors in history, Timur (also known as Tamerlane), lives in the heart of Samarkand in a lavish mausoleum with a massive fluted tile dome. In the 14th-century, he built an empire that rivaled Genghis Khan’s a century earlier, his armies killing an estimated 17 million people, about 5% of the world’s population at the time.

In addition to its architectural heritage, Bukhara also is the shopping capital of the new Silk Road. A sea of vendors is embedded in and around the historic buildings, selling everything from traditional jewelry and hand-made carpets to carvings, silk scarves and clothing, and colorful drawings. You can watch artists, carpet-weavers, tailors, potters and other artisans at work here, and buy directly from them.

The legacy of one of the greatest – and most brutal – conquerors in history, Timur (also known as Tamerlane), lives in the heart of Samarkand in a lavish mausoleum with a massive fluted tile dome. In the 14th-century, he built an empire that rivaled Genghis Khan’s a century earlier, his armies killing an estimated 17 million people, about 5% of the world’s population at the time.

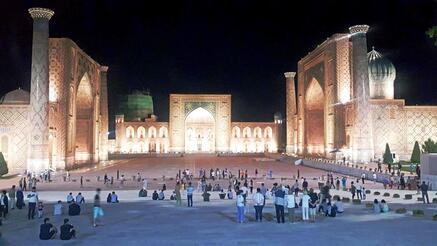

Epic in scale, The Registan is the crowning glory of Samarkand ‒ and arguably the entire Silk Road and all of Central Asia. The domineering trio of madrassas (Islamic centers of learning) built 400-600 years ago in the heart of the traditional commercial center, are massive sentinels of power and faith, and are among the world’s oldest remaining Muslim schools. Seeing only The Registan is reason enough to make the long voyage to Central Asia to see the Big Three destinations of Uzbekistan.

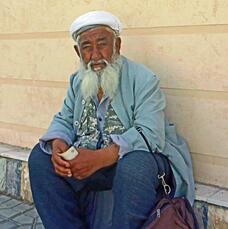

Walking the streets of these ancient hubs, I spent much of my time responding to friendly, passing Uzbeks saying hello with big smiles and asking how I’m doing. Communication was sometimes difficult; I encountered some English speakers but more often used Google Translate in Russian, a lingua franca here; often it was impossible to communicate, other than a quick exchange of greetings. But anyone who understood when I asked a question or for directions would jump into action to help me, often using their phone to locate my destination. If I stopped to read a map, invariably someone would appear wondering if I needed assistance.

Walking the streets of these ancient hubs, I spent much of my time responding to friendly, passing Uzbeks saying hello with big smiles and asking how I’m doing. Communication was sometimes difficult; I encountered some English speakers but more often used Google Translate in Russian, a lingua franca here; often it was impossible to communicate, other than a quick exchange of greetings. But anyone who understood when I asked a question or for directions would jump into action to help me, often using their phone to locate my destination. If I stopped to read a map, invariably someone would appear wondering if I needed assistance.

Hotels often went overboard to assist with my needs and travel plans; the owner of Old Bukhara B&B actually called me as I was en route to Samarkand to ask if my trip was going well, and then called a second time to make sure the driver knew how to get to my next hotel. The greatest joy at hotels though was the breakfast feast that would be set before you, a dozen or more plates usually including egg dishes, yogurt, cheeses, cold cuts, fresh fruits, pastries, Uzbek breads, jams, biscuits, coffee and tea.

Today’s Uzbek kitchen reflects its 1,500-year history as a crossroad of the world. The typical foods – dumplings, soups, stews and pilafs – channel many cultures. Most restaurants serve the same handful of traditional dishes that are mostly mildly flavored and use spices sparingly. While not exciting, this Uzbek comfort food is hearty and satisfying.

Today’s Uzbek kitchen reflects its 1,500-year history as a crossroad of the world. The typical foods – dumplings, soups, stews and pilafs – channel many cultures. Most restaurants serve the same handful of traditional dishes that are mostly mildly flavored and use spices sparingly. While not exciting, this Uzbek comfort food is hearty and satisfying.

For a burst of flavor, I turned to kebabs and shashlik (shishkabab). They are exceptional because of an unbeatable combination: Meat quality is topnotch because animals feed free range on green grass, the meat marinades and kebab mixtures are more intensely spiced than other foods here, and they are cooked over fragrant wood fires.

They are always served with a big mound of very thinly sliced sweet white onion, and I soon looked forward to that sea of chopped bulb because I knew I would be biting into Uzbekistan’s most delicious treat. Everything else paled in comparison, except for the glorious bread.

They are always served with a big mound of very thinly sliced sweet white onion, and I soon looked forward to that sea of chopped bulb because I knew I would be biting into Uzbekistan’s most delicious treat. Everything else paled in comparison, except for the glorious bread.

I often ate a small wheel of non right from the wood-fired oven, so hot I couldn’t hold it, that was melt-in-my-mouth fluffy inside and tantalizingly crispy and caramelized on the outside, especially on top, and accented with savory caraway seeds. This inside-outside contrast is achieved by slapping a disk of dough on the ceiling of the extremely hot oven, and while the bread expands the top becomes searingly crusty and chewy without burning or drying out. My mouth still waters every time I think about an Uzbek non.

For more information on the region, check out the following sites

https://uzbekistan.travel

https://wikitravel.org/en/Uzbekistan

https://againstthecompass.com/en/uzbekistan-travel-guide

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/uzbekistan

https://caravanistan.com/uzbekistan

For more information on the region, check out the following sites

https://uzbekistan.travel

https://wikitravel.org/en/Uzbekistan

https://againstthecompass.com/en/uzbekistan-travel-guide

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/uzbekistan

https://caravanistan.com/uzbekistan

|

Images copyright of the author

Click on any image to enlarge it |