the Intriguing South Caucasus

By Edward Placidi. Edward is a freelance travel writer/photographer who has lived and traveled in 90 countries, including extended overland journeys across Africa, Europe, South America and Asia. He has penned articles for dozens of newspapers, magazines and websites. When not travelling he is whipping up delicious dishes inspired by his Tuscan grandmother who taught him to cook. A passionate Italophile and supporter of the Azzurri (Italian national soccer team), he lives in Los Angeles with his wife Marian.

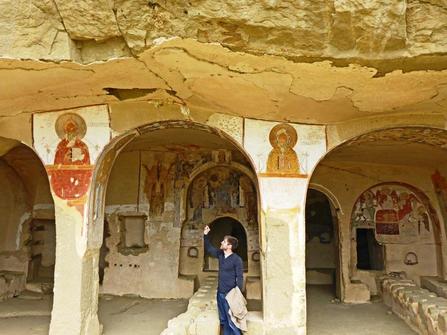

We had arrived at what felt like the edge of the world. A cool wind swept across the remote, boulder-strewn hills to the vast, empty valley below. A huge white eagle abruptly landed on a nearby knoll and observed us with indifference. And above us loomed reclusive Davit Gareji, one of Georgia’s imposing medieval monasteries where thousands of monks once lived an hermetic existence.

We hiked up to a row of cave dwellings whose walls are adorned with stunning, hand-painted religious imagery. Our guide, Beso, was upset when he saw the extent of the damage: “The Azerbaijanis did this. They come and destroy our frescoes in the night because they still claim this land,” he claimed. “We have always had conflicts with each other in this region and always will,” he lamented, and then ticked off a list of skirmishes and brief wars in the South Caucasus in just his 30-something years.

Indeed, the tiny South Caucasus nations of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan have always known siege and tumult, from their internecine squabbles to the machinations and invasions by their powerful neighbors (Turkey, Iran and Russia). But times have changed, at least for now. The mountainous region is peaceful and safe, the people are extremely hospitable and welcoming, the land pulsates with history and attractions, costs are modest, and tourism is blossoming.

I had come from the ancient stone village of Lahic, that appears not to have changed in centuries but in reality is a slowly dissolving time warp in fast-modernizing, oil-rich Azerbaijan. The long tradition of artisanry is fading away: The once-famous carpet makers are gone and only a few coppersmiths remain, their pounding hammers echoing in the narrow lanes. Tourism has arrived with the opening of guest houses, hotels and restaurants catering to Bakuvians escaping to these gloriously beautiful mountains where the hiking is absolutely spectacular.

We hiked up to a row of cave dwellings whose walls are adorned with stunning, hand-painted religious imagery. Our guide, Beso, was upset when he saw the extent of the damage: “The Azerbaijanis did this. They come and destroy our frescoes in the night because they still claim this land,” he claimed. “We have always had conflicts with each other in this region and always will,” he lamented, and then ticked off a list of skirmishes and brief wars in the South Caucasus in just his 30-something years.

Indeed, the tiny South Caucasus nations of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan have always known siege and tumult, from their internecine squabbles to the machinations and invasions by their powerful neighbors (Turkey, Iran and Russia). But times have changed, at least for now. The mountainous region is peaceful and safe, the people are extremely hospitable and welcoming, the land pulsates with history and attractions, costs are modest, and tourism is blossoming.

I had come from the ancient stone village of Lahic, that appears not to have changed in centuries but in reality is a slowly dissolving time warp in fast-modernizing, oil-rich Azerbaijan. The long tradition of artisanry is fading away: The once-famous carpet makers are gone and only a few coppersmiths remain, their pounding hammers echoing in the narrow lanes. Tourism has arrived with the opening of guest houses, hotels and restaurants catering to Bakuvians escaping to these gloriously beautiful mountains where the hiking is absolutely spectacular.

On an afternoon trek, I ascended into lush glades and glens emblazoned with jubilant wildflowers of every color that had exploded to life after the long winter. A magnificent, tiny blue butterfly appeared and then instantly winged away. Not a sound was heard, other than the occasional avian call. I found my way back by negotiating the sea of boulders in the wide riverbed that was a mere stream before the onslaught of the melting snow.

While Lahic is the past in transition, Baku is galloping into the future – a shiny, fast-moving new city of posh public amenities and innovative modern architecture where construction continues unabated. Baku is a showplace proclaiming the country’s burgeoning oil riches, and the rush of energy and exuberance swoops you up and carries you along. The city’s architectural icons are the Flame Towers, a trio of soaring, uber-modern glass buildings with shimmering blue facades that can be seen across the city. Lavish promenades, flowing fountains, and verdant parks and gardens are perfectly maintained by a small army of sweepers. Even the Old City, a historically fascinating maze of ancient palaces, mosques and hammams, has been laboriously restored to a fault, looking almost like a movie set.

While Lahic is the past in transition, Baku is galloping into the future – a shiny, fast-moving new city of posh public amenities and innovative modern architecture where construction continues unabated. Baku is a showplace proclaiming the country’s burgeoning oil riches, and the rush of energy and exuberance swoops you up and carries you along. The city’s architectural icons are the Flame Towers, a trio of soaring, uber-modern glass buildings with shimmering blue facades that can be seen across the city. Lavish promenades, flowing fountains, and verdant parks and gardens are perfectly maintained by a small army of sweepers. Even the Old City, a historically fascinating maze of ancient palaces, mosques and hammams, has been laboriously restored to a fault, looking almost like a movie set.

On the fringes of the new, however, I discovered the real old Baku ‒ of broken stone streets, dilapidated vintage houses with splintering encased-wood balconies, simple neighborhood markets and tea and pastry shops. Zarina Rostacova, a professor at Baku State University, who started a conversation by addressing me in English, told me: “This is old Baku and it is slowly disappearing. They bulldoze entire areas and then build modern, high-rise apartments.” As we walked, at one point she pointed to a large dirt lot several blocks away and said: “That was the latest area to be cleared. New construction will start soon.”

In Yerevan, Armenia’s leafy capital, the vibe is more relaxed and modest. The relatively small center is populated with trendy restaurants, coffee bars, boutiques, verdant parks, walking streets, hookah lounges and myriad outdoor cafes that are the favorite hangouts. The city’s denizens are fashionably dressed (Italian designer boutiques are everywhere) and on the go: From late morning to deep into the night, people are out dining, drinking, shopping and promenading ‒ a thriving daily scene playing out on tree-lined streets, that ratchets up exponentially on Saturday nights when crowds gather in Republic Square to watch the fountains dance to a light, music and water show.

Exploring Yerevan, the quirky statuary jumps out at you, triggering an array of emotions, from bemusement and laughter to astonishment and awe. Each encounter is a whimsical moment of joy: a bulbous blue kiwi that looks like a gargantuan dancing pool toy; an elephant-size ear hanging on the façade of a building; human-like hares dancing on the backs of baby elephants; a featureless, genderless, life-size figure emerging anonymously from a wall; a gigantic reclining woman with voluptuously exaggerated proportions smoking a cigarette by celebrated Colombian sculptor Fernando Botero.

In Yerevan, Armenia’s leafy capital, the vibe is more relaxed and modest. The relatively small center is populated with trendy restaurants, coffee bars, boutiques, verdant parks, walking streets, hookah lounges and myriad outdoor cafes that are the favorite hangouts. The city’s denizens are fashionably dressed (Italian designer boutiques are everywhere) and on the go: From late morning to deep into the night, people are out dining, drinking, shopping and promenading ‒ a thriving daily scene playing out on tree-lined streets, that ratchets up exponentially on Saturday nights when crowds gather in Republic Square to watch the fountains dance to a light, music and water show.

Exploring Yerevan, the quirky statuary jumps out at you, triggering an array of emotions, from bemusement and laughter to astonishment and awe. Each encounter is a whimsical moment of joy: a bulbous blue kiwi that looks like a gargantuan dancing pool toy; an elephant-size ear hanging on the façade of a building; human-like hares dancing on the backs of baby elephants; a featureless, genderless, life-size figure emerging anonymously from a wall; a gigantic reclining woman with voluptuously exaggerated proportions smoking a cigarette by celebrated Colombian sculptor Fernando Botero.

Like Georgia, Armenia is devoutly religious – the two countries claim they were the first Christian nations ‒ and the spectacular monasteries dating as far back as the 7th century are travel highlights.

Climbing into fecund highland valleys of flowering apple, peach and apricot trees brought us to impressive Geghard Monastery, a massive stone complex built into a mountainside on the ruins of a 1st-century citadel. In the musty main chapel, time stood still as kneeling supplicants prayed and brilliantly colored ancient frescoes were revealed by the flickering candle light under a ceiling blackened by centuries of burning wax. The solitary monastery of Khor Vidrop, dramatically perched atop the lone hill of an expansive valley, is defined by a famous backdrop: Mt. Ararat, where the Book of Genesis says Noah’s ark came to rest. Formerly inside Armenia but on the Turkish side of the border today, it’s a national symbol and holy site for Armenians.

Climbing into fecund highland valleys of flowering apple, peach and apricot trees brought us to impressive Geghard Monastery, a massive stone complex built into a mountainside on the ruins of a 1st-century citadel. In the musty main chapel, time stood still as kneeling supplicants prayed and brilliantly colored ancient frescoes were revealed by the flickering candle light under a ceiling blackened by centuries of burning wax. The solitary monastery of Khor Vidrop, dramatically perched atop the lone hill of an expansive valley, is defined by a famous backdrop: Mt. Ararat, where the Book of Genesis says Noah’s ark came to rest. Formerly inside Armenia but on the Turkish side of the border today, it’s a national symbol and holy site for Armenians.

I had arrived in Vardzia to see the famous 12th-century caves carved from the rock of a jutting promontory that evolved into a holy city – with more than 400 rooms, 13 churches, several with impressive frescoes, and 25 wine cellars ‒ inhabited once by some 2,000 monks and where Persian invaders smashed the Georgian army in 1551. But when I walked into the lone tavern in the tiny village, I was instantly waylaid by an indulgent and cherished Georgian tradition. I was ceremoniously given a glass of wine and was suddenly toasting ‒ to whom or what I didn’t know ‒with a group of Georgians. It would be the first of dozens of toasts, numerous glasses of wine, and plate after plate of food. I had stumbled into a ‘Supra’ ‒ the Georgian feasts where vast quantities of wine are downed as they offer a continuous stream of toasts ‒ and I was now an honored guest.

The wine was served by the pitcher – large ones ‒ and we raised our glasses seemingly every 30 seconds, and at one point interlocked arms to gulp full glasses. Most toasts were accompanied by bursts of laughter, but hysteria erupted when they understood ‒ we shared no common language ‒ that I was from California. “Schwarzenegger!” they shouted in unison. “Schwarzenegger!” And we toasted repeatedly to Arnold and California.

A couple of hours into the Supra there was a lull and it seemed things were winding down, but they were only waiting for the pitcher of chacha, the potent (45-55 percent alcohol) Georgian brandy made from grape skins and seeds. And it began all over again.

A couple of hours into the Supra there was a lull and it seemed things were winding down, but they were only waiting for the pitcher of chacha, the potent (45-55 percent alcohol) Georgian brandy made from grape skins and seeds. And it began all over again.

Georgia’s charming capital, Tbilisi, is the new tourism hub of the region, hosting an increasing number of travelers mostly from Russia, Ukraine and the Emirates. Visitors flock to the compact old town with its ever-increasing roster of hotels, restaurants, wine bars, taverns, coffee houses, snack shops and hookah lounges, as well as historic basilicas and the Narikala Fortress looming over the winding streets.

Tbilisi is the jumping-off spot for day trips to historic and scenic sites across the country ‒ such as Borjomi, famed for its signature Georgian mineral water, Mtskheta, the nation’s holiest site teeming with fervent pilgrims, the extraordinary monastery and cave complex of Davit Gareji, and of course Vardzia.

Tbilisi is the jumping-off spot for day trips to historic and scenic sites across the country ‒ such as Borjomi, famed for its signature Georgian mineral water, Mtskheta, the nation’s holiest site teeming with fervent pilgrims, the extraordinary monastery and cave complex of Davit Gareji, and of course Vardzia.

Perhaps the favorite Georgian destination, however, is the wine country of Kakheti, an eden of tree-lined country lanes, groves of fruit trees and flocks of sheep crossing the road, ringed by green-carpeted hills and snow-capped peaks beyond, and dotted with imposing citadels and cathedrals on promontories. Passion for the vine runs deep here. According to archaeological evidence, the Georgians have been making wine since the 4th millennium B.C and drinking is an integral part of their lifestyle today. They also make it differently than anywhere else: grapes are fermented naturally ‒ with skins, seeds and even stems ‒ in terra-cotta pots called qvevri buried in the ground, with nothing added and no aging in oak barrels.

The qvevri system produces unique wines that are generally dense and weighty with generous acidity and tannins. The reds can be so dark they’re almost black, often with notes of dried fruits, while whites are complex, minerally and amber colored. They can be tasted at scores of wineries, from inventive Pheasant’s Tears Vineyard in the photogenic, red-roofed hilltop town of Sighnaghi, to huge Khareba Winery with its miles of underground wine-storage tunnels, to home-based, boutique Milorauli Vineyard with an 85-year-old vine in the garden.

The qvevri system produces unique wines that are generally dense and weighty with generous acidity and tannins. The reds can be so dark they’re almost black, often with notes of dried fruits, while whites are complex, minerally and amber colored. They can be tasted at scores of wineries, from inventive Pheasant’s Tears Vineyard in the photogenic, red-roofed hilltop town of Sighnaghi, to huge Khareba Winery with its miles of underground wine-storage tunnels, to home-based, boutique Milorauli Vineyard with an 85-year-old vine in the garden.

The Georgians claim that with their organic wine-making method you can drink as much as you want without getting a hangover. Would I really have no ill affects after the Supra in Vardzia? The next morning, the sun was shining and my head was clear. I felt great. And I hiked up to the caves to explore.

For more information, go to

www.georgia.travel www.azerbaijan.travel www.tourismarmenia.org

For more information, go to

www.georgia.travel www.azerbaijan.travel www.tourismarmenia.org

|

Images copyright of the author

Click on any image to enlarge it |