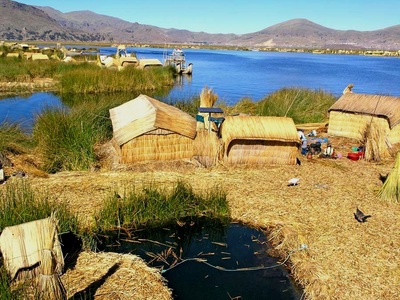

lake titicaca's floating islands

By Solange Hando. Solange is a professional travel journalist and photographer, editor, public speaker and facilitator. She has contributed to National Geographic and Reader's Digest travel books and published features in 96 titles worldwide. She travels widely but her specialist subjects are Bhutan, where she attended the coronation, Nepal and France. She is a member of the British Guild of Travel Writers, Travel Writers UK and the International Travel Writers Alliance. Her latest book is the Berlitz Guide to Bhutan. She is also the author of, 'Be a Travel Writer, Live your Dreams, Sell your Features' which has been endorsed by Hilary Bradt (founder of the Bradt travel guides) and best selling author Simon Whaley. Search for Solange Hando at http://www.amazon.co.uk

At 12 507 feet, Lake Titicaca appears like a dream, framed by pastel-coloured hills shimmering at the water’s edge under the crisp Andean sky. Stretching for over 100 miles and into Bolivia on its eastern side, fed by five rivers and numerous streams, it’s said to be the world’s highest navigable lake. The nature reserve created in 1978 protects 60 species of native birds and in the sheltered bay of Puno, the Uros Indians live peacefully on man-made islands. They were here long before the Incas built Machu Picchu but on their flimsy abodes ignored by the Conquistadores, they have outlived them for over 400 years.

Soon after dawn, the first tourist boat sets off from Puno towards the nearest of 40 islands or so sprinkled around the bay. Built with local totora reeds, they glow coppery gold in the early sun and before long, the islanders begin to stir. Smoke rises from the huts, pots and pans tinkle in the semi- darkness, a man paddles in search of fresh reeds to strengthen or extend his domain and meet growing family needs. The reeds are cut near the shore, towed back then assembled and anchored on the spot. It’s an ongoing task for the ‘people of the lake’, 2000 of them though it never feels like it. Sailing around clusters of tiny islands, you spot a few huts on this one, a shrine on that one, a school on another, a clinic or a couple of craft stalls. The islands are fully movable but if you can’t jump across to see your neighbour, there are plenty of reed boats to travel around. Most stunning are the majestic dragon-headed vessels gliding silently on blue waters, ready to carry a handful of wide-eyed visitors.

Soon after dawn, the first tourist boat sets off from Puno towards the nearest of 40 islands or so sprinkled around the bay. Built with local totora reeds, they glow coppery gold in the early sun and before long, the islanders begin to stir. Smoke rises from the huts, pots and pans tinkle in the semi- darkness, a man paddles in search of fresh reeds to strengthen or extend his domain and meet growing family needs. The reeds are cut near the shore, towed back then assembled and anchored on the spot. It’s an ongoing task for the ‘people of the lake’, 2000 of them though it never feels like it. Sailing around clusters of tiny islands, you spot a few huts on this one, a shrine on that one, a school on another, a clinic or a couple of craft stalls. The islands are fully movable but if you can’t jump across to see your neighbour, there are plenty of reed boats to travel around. Most stunning are the majestic dragon-headed vessels gliding silently on blue waters, ready to carry a handful of wide-eyed visitors.

Stepping ashore on a bouncy patch of reeds may be unnerving but no one seems to mind. ‘Please come inside,’ says a man with a bright woolly hat, ‘this is my home.’ It’s just one room, no furniture, but there are rugs on the floor and a small black and white television in the corner. Outside the sun is dazzling, the air is cold but ‘Mama’ is used to it. An imposing figure in ample skirt and traditional bowler hat, she has lit the fire on a bed of stones and proudly shows the fish caught by her man that morning. Nothing grows on the reeds but you can catch fish and ducks, for meat and eggs, chew the white root of a reed or two and head for the market in Puno to sell embroidered cloth, knitwear and trinkets and buy whatever you need.

Historians believe the Uros set up home on the lake to escape trouble on land but legend says otherwise. It claims they were here before the dawn of time, protected by ‘black blood’ when the earth was ‘dark and cold’, and few today would wish to change their traditional way of life. A cell phone may ring now and then but somewhere on the edge of the water, a child plays an Andean flute as a sudden breeze sends ripples across the reeds. The tourist boat heads back to the mainland then slowly, on the ‘Black Puma’ lake, the islands vanish, floating like a mirage between water and sky.

|

Images copyright of the Author

Click image to enlarge |