Ghana

Travelling the Ghanaian Way

By Edward Placidi. Edward is a freelance travel writer/photographer who has lived and traveled in 90 countries, including extended overland journeys across Africa, Europe, South America and Asia. He has penned articles for dozens of newspapers, magazines and websites. When not travelling he is whipping up delicious dishes inspired by his Tuscan grandmother who taught him to cook. A passionate Italophile and supporter of the Azzurri (Italian national soccer team), he lives in Los Angeles with his wife Marian.

Walter, a front desk manager at the Ezime Guest House in the town of Ada Foah, epitomized the Ghanaian spirit. I was heading to the village of Anyanui to see the big weekly country market bringing together farmers and traders from throughout the area. I had heard motorized canoes made the journey, piercing the waters of the mouth of the mighty Volta River where it meets the Atlantic, and I asked Walter where to find one. He of course had to take me personally to a landing on the riverfront, about a 10-minute walk, where he negotiated my passage and within a few minutes I was on my way. It was the Ghanaian way.

Ghana doesn’t have the impressive wildlife of East or Southern Africa, the extraordinary ancient monuments of Egypt, or even the intriguing walled royal cities of Morocco. But it does have an unsurpassed indomitable spirit, manifested day-to-day in the warmth, smiles and hospitality of its people. The Ghanaians make travel in their country a joy, and relatively easy.

The first impression is gleeful and jubilant: The people of Ghana are decked out in a happy kaleidoscope of radiant colors, patterns and prints, particularly the women who usually wrap their heads as well as their bodies in bright and joyful cloth.

As you travel around the country, the kindheartedness is palpable. While most people of course just go about their business, frequently I was greeted with a nod, a smile or a bright hello – and sometimes “Awaaba” (welcome). But anyone I stopped to ask directions or a question invariably went out of their way to help. One day, I needed a new charger for my phone and randomly asked a young man on the street in Accra, the capital. He thought for a second, then said follow me. He took me to a kiosk several blocks away, where I found what I was looking for.

Trotros (the mini-buses that go everywhere) and shared taxis (that take up to four passengers on a set route) don’t just drop you off; they ask where you are going and if you’re continuing on they find you your next transport and transition you to the new vehicle. Travelers boarding a vehicle often say good morning or afternoon to the other passengers. It’s all very courteous… but fraught with danger.

One of the pleasures of Ghana is that you feel so safe; crime against tourists is rare and petty. The greatest danger may be the drivers – while polite to passengers, they are demons behind the wheel, driving their old vehicles that are way beyond their prime at dangerously high speeds. So speedbumps are everywhere, on city streets, at the entrances to towns, along highways. It seems you never drive more than 5-10 minutes without having to slow for a speedbump. Driving intoxicated is a problem too and warnings signs litter highways. One typical sign asks: “Driving drunk? Choose One: Jail, Hospital or Morgue.”

The first impression is gleeful and jubilant: The people of Ghana are decked out in a happy kaleidoscope of radiant colors, patterns and prints, particularly the women who usually wrap their heads as well as their bodies in bright and joyful cloth.

As you travel around the country, the kindheartedness is palpable. While most people of course just go about their business, frequently I was greeted with a nod, a smile or a bright hello – and sometimes “Awaaba” (welcome). But anyone I stopped to ask directions or a question invariably went out of their way to help. One day, I needed a new charger for my phone and randomly asked a young man on the street in Accra, the capital. He thought for a second, then said follow me. He took me to a kiosk several blocks away, where I found what I was looking for.

Trotros (the mini-buses that go everywhere) and shared taxis (that take up to four passengers on a set route) don’t just drop you off; they ask where you are going and if you’re continuing on they find you your next transport and transition you to the new vehicle. Travelers boarding a vehicle often say good morning or afternoon to the other passengers. It’s all very courteous… but fraught with danger.

One of the pleasures of Ghana is that you feel so safe; crime against tourists is rare and petty. The greatest danger may be the drivers – while polite to passengers, they are demons behind the wheel, driving their old vehicles that are way beyond their prime at dangerously high speeds. So speedbumps are everywhere, on city streets, at the entrances to towns, along highways. It seems you never drive more than 5-10 minutes without having to slow for a speedbump. Driving intoxicated is a problem too and warnings signs litter highways. One typical sign asks: “Driving drunk? Choose One: Jail, Hospital or Morgue.”

The ubiquitous police checkpoints on the highways were another potential danger – but mostly for Ghanaians. On a few occasions I was asked if I was a tourist, otherwise I was ignored. But several times a Ghanaian was pulled off a trotro, not to return, and often I watched the driver pass a small bill to ensure safe passage. A reverend I was sitting next to on one trotro ride offered a xenophobic explanation for all the checkpoints: “There are many people around from Burkino Fasso doing bad things and the police need to control the problem.” I surmised that he didn’t want me to think that Ghanaians were involved in anything untoward.

I took Ghana’s grand ferry journey, a 30-hour odyssey on the MV Yapei Queen traversing the length of Lake Volta, the world’s largest man-made lake. Rumana Ahmed, the “Queen of the Yam Traders,” was a towering and luminous presence on board. She stood apart from the poor and modest passengers with her expensive clothing, fine silver necklaces and earrings, huge size, big laugh and bulging confidence.

Rumana circulated the ferry mirthfully tossing out comments like a strolling comic, getting laughs and smiling retorts in response. At one point, seeing me staring at my tablet screen, she asked me what I was doing. When I explained I was reading “My First Coup d’Etat” by former Ghanaian president John Mahama, she erupted in effusive joy. “I love that man…he was best president,” she declared, and we were friends for the remainder of the journey. Originally from Burkino Fasso, she has been in Ghana 25 years trading yams on the ferry route, picking up product at several ports and shipping them to Accra. “Very good business, ” she told me in her broken English with a guffaw.

I took Ghana’s grand ferry journey, a 30-hour odyssey on the MV Yapei Queen traversing the length of Lake Volta, the world’s largest man-made lake. Rumana Ahmed, the “Queen of the Yam Traders,” was a towering and luminous presence on board. She stood apart from the poor and modest passengers with her expensive clothing, fine silver necklaces and earrings, huge size, big laugh and bulging confidence.

Rumana circulated the ferry mirthfully tossing out comments like a strolling comic, getting laughs and smiling retorts in response. At one point, seeing me staring at my tablet screen, she asked me what I was doing. When I explained I was reading “My First Coup d’Etat” by former Ghanaian president John Mahama, she erupted in effusive joy. “I love that man…he was best president,” she declared, and we were friends for the remainder of the journey. Originally from Burkino Fasso, she has been in Ghana 25 years trading yams on the ferry route, picking up product at several ports and shipping them to Accra. “Very good business, ” she told me in her broken English with a guffaw.

In Accra, street life is raw and intimate. The entire center is a sprawling marketplace, and among the densest anywhere, the cacophony and action reaching a feverish, senses-popping intensity: The cries of countless hawkers shouting out their products and prices, revving engines and blasting car horns competing with blaring music from boom boxes and speakers. A crush of people – countless shoppers squeezing among the throngs, armies of sellers staking out positions to best hawk their wares – reduces movement to a crawl. Vehicles of all sorts inching through the crowds. Explosions of color, from the bright and fanciful prints and patterns of the people’s clothing to the vast array of products and fresh produce. Pungent odors rise from the decaying mix of trash and organic material carpeting the ground.

Ghana is a land of specialists. Everyone on the streets seems to be selling something, but only one type of product : A luggage hawker is carrying one suitcase in each hand and has two balanced on his head. Cloth sellers have hands full of materials and many layers draped over shoulders and arms. A mango peddler is balancing a huge bowl on her noggin filled with dozens of only that type of fruit.

In today’s Ghana, the past is largely obscured; the people are living in the moment, struggling to feed and clothe their families. In Accra, for example, the historic forts and buildings along the oceanfront are dilapidated and forgotten, and the crowds and markets noticeably absent there. But there are exceptions. In Kumasi, Ghana’s second city, the Royal Palace unfurls the history and tradition largely unseen in modern Ghana. Visitors are immersed in the daily life of the royal dynasty of Ghana’s powerful and long-dominant Ashanti tribe. The current king lives in a new palace next door, but in the original palace time has been frozen with every room filled with the personal effects and household furnishings of past kings and queens, meshed with historical photos and materials documenting the struggles with the European colonial powers.

Ghana is a land of specialists. Everyone on the streets seems to be selling something, but only one type of product : A luggage hawker is carrying one suitcase in each hand and has two balanced on his head. Cloth sellers have hands full of materials and many layers draped over shoulders and arms. A mango peddler is balancing a huge bowl on her noggin filled with dozens of only that type of fruit.

In today’s Ghana, the past is largely obscured; the people are living in the moment, struggling to feed and clothe their families. In Accra, for example, the historic forts and buildings along the oceanfront are dilapidated and forgotten, and the crowds and markets noticeably absent there. But there are exceptions. In Kumasi, Ghana’s second city, the Royal Palace unfurls the history and tradition largely unseen in modern Ghana. Visitors are immersed in the daily life of the royal dynasty of Ghana’s powerful and long-dominant Ashanti tribe. The current king lives in a new palace next door, but in the original palace time has been frozen with every room filled with the personal effects and household furnishings of past kings and queens, meshed with historical photos and materials documenting the struggles with the European colonial powers.

European trading outposts dating from the 15th century at Cape Coast and its nearby sister fishing port of Elmina evolved into hubs of the slave trade. Today, visitors can walk the warren of alleys and narrow streets in the historic and bustling old centers and take the informative but chilling tour of the seaside castle at each port where slaves were held before being shipped to the New World. I descended into the dungeons of these mighty fortresses protected by rows of cannons and learned about the suffering that occurred there, but the message of the guides, rather than harboring lingering resentment, emphasized that this was the past and today we are all united as one against such inhumanity. It was heartwarming.

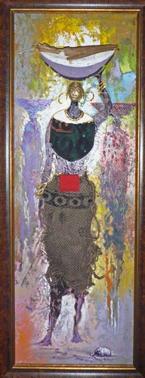

In Kumasi, at the crafts market at the National Cultural Centre, I wandered into the studio of Philip Panford, an up-and-coming artist who experiments with adding other media – including metal, cloth and wood – to oil paintings on canvas to give them a three-dimensional profile. His works sizzled with emotion, and like so many things Ghanaian, his piece hanging in my house is a blast of colorful joy.

For more information:

http://wikitravel.org/en/Ghana

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/ghana

In Kumasi, at the crafts market at the National Cultural Centre, I wandered into the studio of Philip Panford, an up-and-coming artist who experiments with adding other media – including metal, cloth and wood – to oil paintings on canvas to give them a three-dimensional profile. His works sizzled with emotion, and like so many things Ghanaian, his piece hanging in my house is a blast of colorful joy.

For more information:

http://wikitravel.org/en/Ghana

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/ghana

|

All images copyright of the author

Click on any image to enlarge it |