El salvador

By Malcolm Tattersall. Mal has spent a lifetime working in various journalistic roles on local, regional and national newspapers in Britain and Ireland. Widely travelled, especially in Latin America and Africa (where he once found himself embroiled in a military coup and another time got kissed by a giraffe). Now semi-retired, Mal whiles away his time travelling, writing and drinking beer (although not necessarily in that order).

My normally-smiling guide Julio recoils in shock. He shakes his head, wrinkles his nose in disgust, and raises his hands in mock horror. You’d think I’d insulted the country’s president or his wife.

In fact all I did was splash a drop of milk into my freshly-brewed coffee.

“Would you,” Julio finally splutters, giving me a rather condescending look, “pour Pepsi into a fine 20-year old malt whisky?” Er no, I admit, I certainly would not. “Well,” he scolds me, “it’s just as heretical to add milk to a good cup of coffee.”

Hmm, Julio has a point; they take their coffee seriously in El Salvador. Not only is the volcanic soil ideal for growing what the locals call the “el grano d’oro” – or the grain of gold – but it has shaped the country’s history, both good and bad, over the centuries.

Coffee aficionados, who happily pay up to $90 a lb for the best local beans, talk in hushed tones like wine buffs about “subtle chocolate flavours” and “hints of honey, berries or fruits”, depending on just where the stuff grew. Higher up in the mountains, where the temperature is slightly cooler, is reckoned the best.

In fact all I did was splash a drop of milk into my freshly-brewed coffee.

“Would you,” Julio finally splutters, giving me a rather condescending look, “pour Pepsi into a fine 20-year old malt whisky?” Er no, I admit, I certainly would not. “Well,” he scolds me, “it’s just as heretical to add milk to a good cup of coffee.”

Hmm, Julio has a point; they take their coffee seriously in El Salvador. Not only is the volcanic soil ideal for growing what the locals call the “el grano d’oro” – or the grain of gold – but it has shaped the country’s history, both good and bad, over the centuries.

Coffee aficionados, who happily pay up to $90 a lb for the best local beans, talk in hushed tones like wine buffs about “subtle chocolate flavours” and “hints of honey, berries or fruits”, depending on just where the stuff grew. Higher up in the mountains, where the temperature is slightly cooler, is reckoned the best.

We’re sipping a highly-prized variety called “Bourbon” at a little café run by Jonatan Mendoza, the country’s champion barista for the last two years, in the rather pretty town of Ataco, sitting astride El Salvador’s spectacular Ruta de las Flores through the western mountains.

It is only a two-hour drive, although it seems a million miles, away from the little seaside village of Playa El Tunco where I breakfasted that morning while watching some 50 young surfers, riding huge Pacific waves as the glorious dawn sun rose behind me.

It is only a two-hour drive, although it seems a million miles, away from the little seaside village of Playa El Tunco where I breakfasted that morning while watching some 50 young surfers, riding huge Pacific waves as the glorious dawn sun rose behind me.

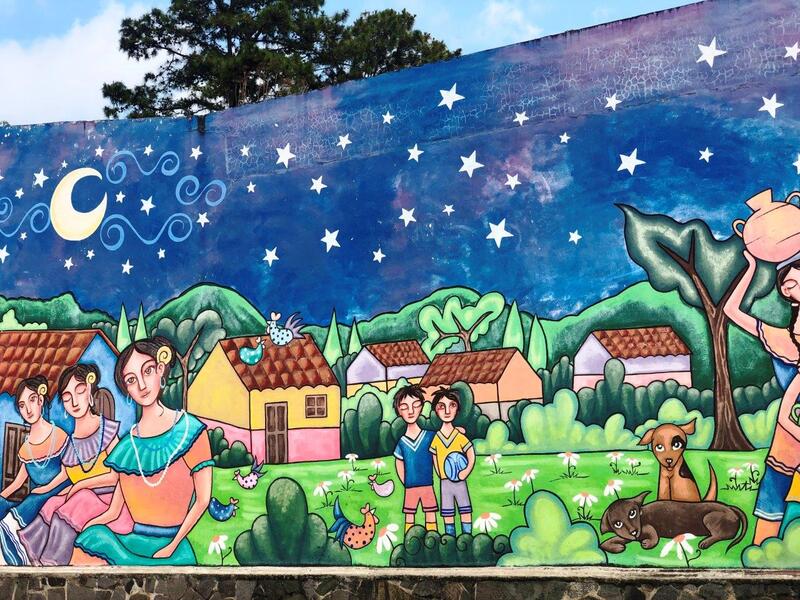

Now I stare out through the window at brighty-coloured, primitive murals adorning the walls of the colonial era buildings, many turned into arts and crafts shops, while in the cobbled street a mangy dog cockily raises its leg against a rickety wooden cart laden with flowers.

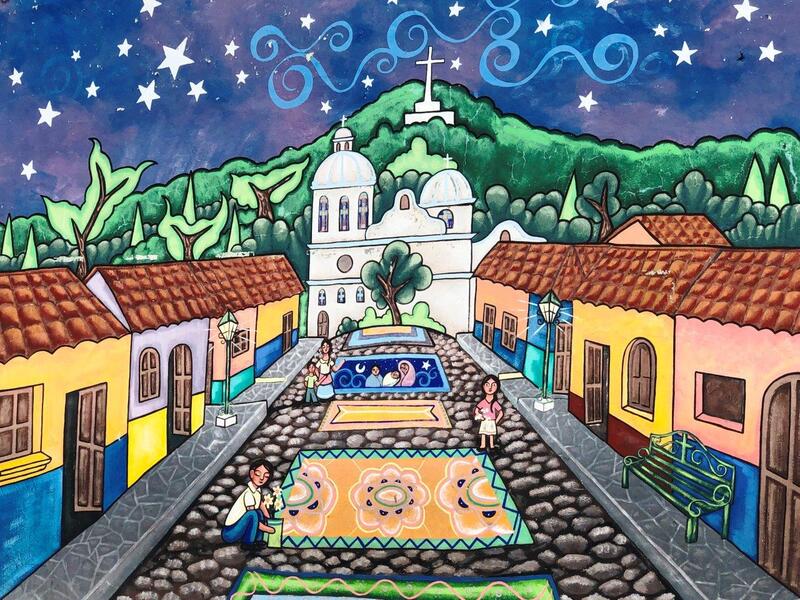

Then a silver pick-up truck, pressed into service as a makeshift hearse with an ornately-carved wooden coffin balanced precariously on the back, backfires and stutters past, hymns blaring from its cab momentarily drowning out the bells of the Church of the Immaculate Conception which are tolling in anticipation of the cortege’s arrival.

The cafe, though, has no murals. Starbucks this ain’t. It’s minimalist and slightly austere, rather like being back in a school laboratory; for coffee-making, it seems, is both a science and art.

The cafe, though, has no murals. Starbucks this ain’t. It’s minimalist and slightly austere, rather like being back in a school laboratory; for coffee-making, it seems, is both a science and art.

To make mine, Jonatan painstakingly weighs 15gms of freshly-ground coffee grains before spooning it into a carefully arranged filter paper. Then slowly in a deliberate clockwise motion, he pours out 180gms of water, heated to exactly 94C, from an odd-looking kettle with a thin crooked spout.

I drink it a tad sheepishly, desperately trying to discern “hints of honey or berries”, anything that I can remark upon and perhaps help atone for my shame at being the “man who added milk to El Salvador’s top barista’s finest brew”.

But all I taste is rather lovely coffee. So instead I thank Jonatan, buy two bags of “Bourbon” to take home, and say goodbye.

I drink it a tad sheepishly, desperately trying to discern “hints of honey or berries”, anything that I can remark upon and perhaps help atone for my shame at being the “man who added milk to El Salvador’s top barista’s finest brew”.

But all I taste is rather lovely coffee. So instead I thank Jonatan, buy two bags of “Bourbon” to take home, and say goodbye.

Just outside Ataco we call at one of the country’s most famous coffee plantations, the El Carmen Estate. For $6 (El Salvador uses the US currency) you can take an hour’s tour to learn how the beans get from the trees into your cuppa. A longer three-hour $25 tour includes a morning snack, lunch and another bag of coffee to take home.

This is La Ruta de las Flores – literally the road of the flowers – snaking through the mountains, past charming little towns and villages like Ataco and Juayua, with their colourful markets and picturesque churches, even if there is a slightly uneasy compromise between Catholicism and the indigenous Pipil people’s traditional beliefs.

Busking in the main square at Nahuizalco is a sombrero-wearing campesino playing a traditional wooden marimba. One of his sons scrapes out a rhythm on an odd-looking metal cylinder called a guira, while the other two strum guitars. I slip them a dollar and, delighted, they launch into a haunting love song.

Carry on just a little further up the road and you’ll find yourself in neighbouring Guatemala, but it would be a pity to leave El Salvador so soon. There’s much more to see and experience yet in this Central American country that proudly boasts it “is great like our people”.

The capital San Salvador, for a start. Not long ago large areas were a no-go area for many locals, let alone nervous tourists, and there are still parts you perhaps wouldn’t want to linger with your grannie after nightfall.

But you could say the same thing about London and most other cities and during four years as mayor Nayib Bukele sorted out the drug gangs, cleaned up the streets and put a smile back on the city’s face. Now 37-year-old Bukele has been elected the country’s president after standing on an anti-corruption ticket and is vowing to do the same for the whole country.

Salvadoreans, sick of the country’s undeserved negative image, are desperate to believe him. I really hope he succeeds too. For despite the country’s past reputation and some of the stories I heard before going there, I never once felt in any danger. On the contrary, people couldn’t have been friendlier and more hospitable.

Indeed one lunchtime while dining with Julio, we bumped into a group of British tourists who had already visited several Central American countries as part of an organised tour. So I asked them which had been their favourite.

Every one replied without hesitation: “El Salvador”.

This is La Ruta de las Flores – literally the road of the flowers – snaking through the mountains, past charming little towns and villages like Ataco and Juayua, with their colourful markets and picturesque churches, even if there is a slightly uneasy compromise between Catholicism and the indigenous Pipil people’s traditional beliefs.

Busking in the main square at Nahuizalco is a sombrero-wearing campesino playing a traditional wooden marimba. One of his sons scrapes out a rhythm on an odd-looking metal cylinder called a guira, while the other two strum guitars. I slip them a dollar and, delighted, they launch into a haunting love song.

Carry on just a little further up the road and you’ll find yourself in neighbouring Guatemala, but it would be a pity to leave El Salvador so soon. There’s much more to see and experience yet in this Central American country that proudly boasts it “is great like our people”.

The capital San Salvador, for a start. Not long ago large areas were a no-go area for many locals, let alone nervous tourists, and there are still parts you perhaps wouldn’t want to linger with your grannie after nightfall.

But you could say the same thing about London and most other cities and during four years as mayor Nayib Bukele sorted out the drug gangs, cleaned up the streets and put a smile back on the city’s face. Now 37-year-old Bukele has been elected the country’s president after standing on an anti-corruption ticket and is vowing to do the same for the whole country.

Salvadoreans, sick of the country’s undeserved negative image, are desperate to believe him. I really hope he succeeds too. For despite the country’s past reputation and some of the stories I heard before going there, I never once felt in any danger. On the contrary, people couldn’t have been friendlier and more hospitable.

Indeed one lunchtime while dining with Julio, we bumped into a group of British tourists who had already visited several Central American countries as part of an organised tour. So I asked them which had been their favourite.

Every one replied without hesitation: “El Salvador”.

|

Images copyright of the author

Click on any image to enlarge it |